Published:

Unlike anywhere else in the world, most judges in the United States today are elected. But it hasn’t always been this way. Over the past two centuries, the American states have taken a variety of different paths, alternating through a variety of elective and appointive methods. Opponents of judicial elections charge that these institutions detract from judicial independence, harm the legitimacy of the judiciary, and put unqualified jurists on the bench; those who support judicial elections counter that, by publicly involving the American people in the process of judicial selection, judicial elections can enhance judicial legitimacy. To say this has been an intense debate of academic, political, and popular interest is an understatement.

Surprisingly little attention has been paid by scholars and policymakers to how these institutions affect legal development. Using the enormous dataset of state supreme court opinions CAP provides, we examined one small piece of this puzzle: whether opinions written by elected judges tend to be more well-grounded in law than those written by judges who will not stand for election. This is an important topic. Given the important role that the norm of stare decisis plays in the American legal system, opinions that cite many existing precedents are likely to be perceived as persuasive due to their extensive legal reasoning. More persuasive precedents, in turn, are more likely to be cited and increase a court’s policymaking influence among its sister courts.

State Courts’ Use of Citations Over American History

The CAP dataset provides a particularly rich opportunity to examine state courts’ usage of citations because we can see how citation practices vary as the United States slowly builds its own independent body of caselaw.

We study the 52 existing state courts of last resort, as well as their parent courts. For example, our dataset includes cases from the Tennessee Supreme Court as well as the Tennessee Supreme Court of Errors and Appeals, a court that was previously Tennessee’s court of last resort. We exclude the decisions of the colonial and territorial courts, as well as decisions from early courts that were populated by legislators, rather than judges.

The resulting dataset contains 1,702,404 cases from 77 courts of last resort. The three states with the greatest number of cases in the dataset are Louisiana (86,031), Pennsylvania (70,804), and Georgia (64,534). Generally, courts in highly populous states, such as Florida and Texas, tend to carry a higher caseload than those who govern less populous states, such as North and South Dakota.

To examine citation practices in state supreme courts, we first needed to extract citations from each state supreme court opinion. For this purpose, we utilize the LexNLP Python package released by LexPredict, a data-driven consulting and technology firm. In addition to parsing the citation (i.e. 1 Ill. 19), we also extract the report the opinion is published in and the court of the case cited (i.e. Illinois Supreme Court). Most state supreme court cases— about 68.7% of majority opinions greater than 100 words—cite another case. About one-third of cases cite between 1 and 5 other cases while about 5% of cases cite 25 or more other cases. The number of citations in an opinion trends upward with time, as Figure 1 shows.

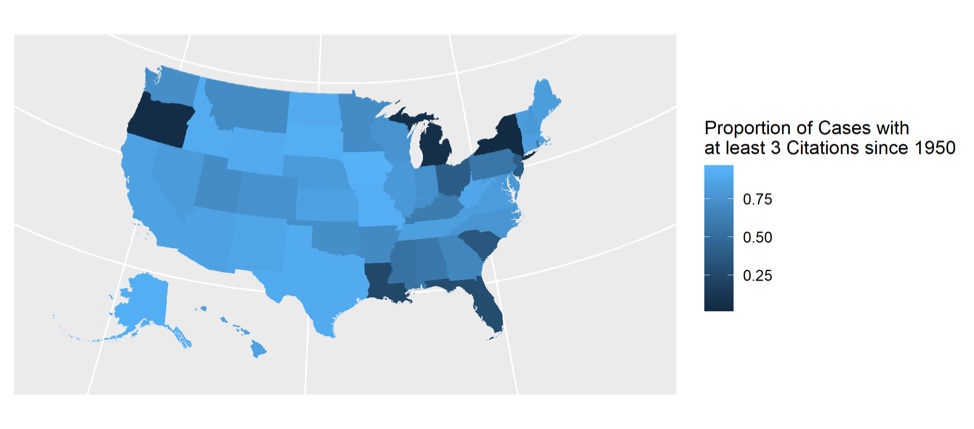

The number of citations in a case varies by state, as well. Some state courts tend to write opinions with a greater number of citations than other state courts. Figure 2 presents the proportion of opinions (with at least 100 words) in each state with at least three citations since 1950. States like Florida, New York, Louisiana, Oregon, and Michigan produce the greatest proportion of opinions with less than three citations. It may not be coincidence that Louisiana and New York are two of the highest caseload state courts in the country; judges with many cases on their dockets may be forced to publish opinions more quickly with less research and legal writing allocated to citing precedent. Conversely, cases with low caseloads like Montana and Wyoming produce the greatest proportion of cases with at least three citations. When judges have more time to craft an opinion, they produce opinions that are more well-grounded in existing precedent.

Explaining Differences in State Supreme Court Citation

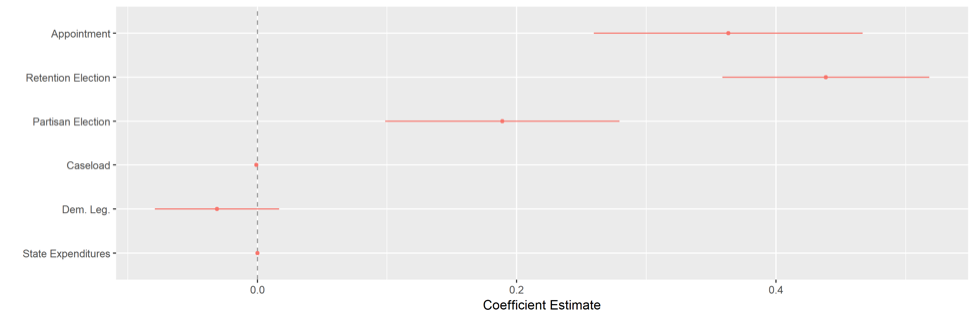

We expected that the number of citations included in a state supreme court method would vary based on the method through which a state supreme court’s justices are retained. We use linear regression to model the median number of citations in a state-year as a function of selection method, caseload, partisan control of the state legislature, and general state expenditures. We restrict the time period for this analysis to the 1942-2010 period.

The results are shown in Figure 3. Compared to judges who face nonpartisan elections, judges who are appointed, face retention elections, and face partisan elections include more citations in their opinions. In appointed systems, the median opinion contains about 3 more citations (about three-fifths of a standard deviation shift) than in nonpartisan election systems. In retention election systems, the median opinion contains almost 5 more citations (about a full standard deviation shift in citations) than in nonpartisan election systems. Even in partisan election systems, the median opinion contains a little less than 3 more citations.

Some Conclusions

These differences represent the potential for drastic consequences for implementation and broader legal development based on the type of judicial selection method in a state. Because opinions with more citations tend, in turn, to be more likely to be cited in the future, the relationship we have uncovered between selection method and opinion quality suggests that judicial selection and retention methods have important downstream consequences for the relative influence of state supreme courts in American legal development. These consequences are important for policymakers to consider as they consider altering the methods by which their judges reach the bench.