Authors:

Published:

This piece is adapted from a keynote talk I gave at Innovación y Experiencia del Usuario at Universidad Católica de Argentina on November 1, 2023.

I was asked to give a talk on the subject of “disruptive innovation in libraries,” which isn’t necessarily the phrase I would choose to describe our work, but I enjoyed using that lens to explore the changes all libraries are going through.

If you want to skip around, Part 1 explores the disruptive changes libraries are experiencing with the arrival of the internet over the last forty years; Part 2 proposes a new mission for libraries in reweaving cultural memory for the internet age; and Part 3 outlines what I’ve learned so far about leading “disruptive innovation” within large, established institutions.

When I think about disruptive innovation in libraries I think about two stories.

Christopher Langdell

One is the story of Christopher Langdell, who reinvented the library where I work when he became dean in 1870.

Langdell changed everything over the course of a few years: different budgets, different physical architecture, different staff, different patrons, different rules. And he did all of that by announcing a different mission for the library. He announced: “The Library is to us what a laboratory is to the chemist or the physicist, and what the museum is to the naturalist,” meaning that the purpose of having a law library is to have the specimens that make it possible to learn and practice the law. He then made all of his choices by asking what would make sure that Harvard Law School had the world’s best laboratory for conducting law — for example, by having one copy of everything, and enough copies of the popular things that everyone could get their hands on one.

His changes were deeply disruptive: he described them as changes of “so radical a character that they have produced a very complete revolution in the Library in almost every particular.” And he acknowledged in his annual report that they caused “more or less temporary inconvenience and embarrassment,” which I think is annual report language for something that caused a great deal of chaos and disruption.

But the disruptive changes worked, because they made the library essential to the law school: he wrote that “without the library, the School would lose its most important characteristics, and indeed its identity.” This was true — the law library became a primary reason for people to go to Harvard and for Harvard to be a premier law school.

(These quotes all from Richard Danner’s excellent article The Legacies of Langdell and His Metaphor.)

For those of us who came afterward, therefore, much of our job was to make sure that Langdell’s mission at the library continued to be carried out; we had to make sure that the people who came after us did about the same, or a bit better, than the people who came before us.

This is the distinction between “disruptive innovation” and “sustaining innovation” — sustaining innovation improves your existing services (and everyone tends to like it), while disruptive innovation adopts new services backed by a new mission (and it is risky, and in some cases simply a bad idea).

Langdell’s story illustrates one side of disruptive innovation: when you choose a new mission to better serve your values.

Wikipedia

The second story is the transition from paper encyclopedias to Wikipedia, which I’m using as a shorthand for the many changes that libraries have gone through with the arrival of the internet.

Before the internet, encyclopedias were essential, and so they were one reason libraries were essential: if you wanted to know a fact, you had to look it up, and if you didn’t have an encyclopedia at home, you had to get yourself to a library. Wikipedia changed that: you no longer had to go to a library to look up a fact.

Libraries are still valuable after Wikipedia — for evidence see the Wikipedia page that begins “Academic Research Libraries and Wikipedia are natural allies. Really.” We can help you understand what you’re seeing on the internet, check whether it is reliable, and find resources to expand your knowledge. If you care about the answer you should check with us. But we are no longer essential.

And because we’re libraries, we don’t even get to be mad about that! As long as you can solve your knowledge problems better than before, we are thrilled.

This is the other kind of disruptive innovation: the innovation that happens to you from outside, when something about the world changes so that pursuing your mission no longer best serves your values.

There are lots of variations of this story, like the arrival of digital journals, open journals, and preprint servers in academic libraries. And there are lots of other stories to tell about Wikipedia — the reasons knowledge experts had to be justifiably skeptical of it as a resource, the miracle that it worked as well as it did, the role libraries played in making it possible, etc.

But for purposes of this talk, “Wikipedia” is shorthand for something we need to get in our bones:

- Patrons are finding knowledge in all kinds of new ways that better solve their problems.

- Those new ways might seem strange or even broken to us, but we don’t get to tell people that they are solving their problems wrong.

- New ways to solve problems can make us fundamentally less valuable. Patrons would suffer less if libraries vanished tomorrow, because Wikipedia exists.

- This is not the last change; new ways to solve problems are emerging faster, not slower. (See: AI.)

The trap: libraries are less indispensable than they have ever been

So here’s the thing we’re grappling with in library work: many forms of library service are no longer essential. We can no longer be satisfied by making sure that the next generation does a bit better than the last generation.

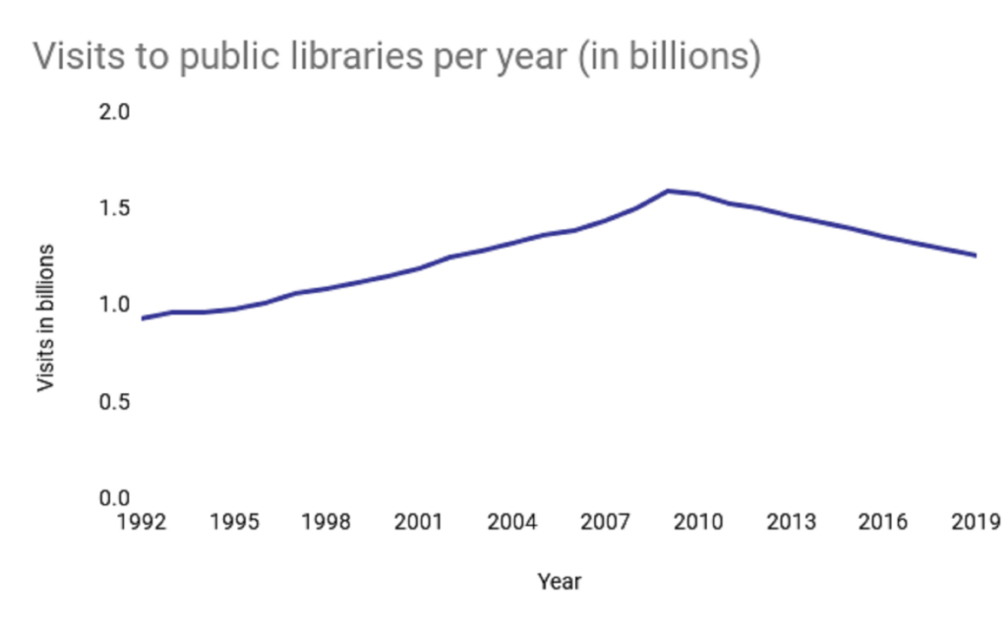

Every library has graphs shaped something like this, which shows a sharp change in visits to US public libraries around 2009:

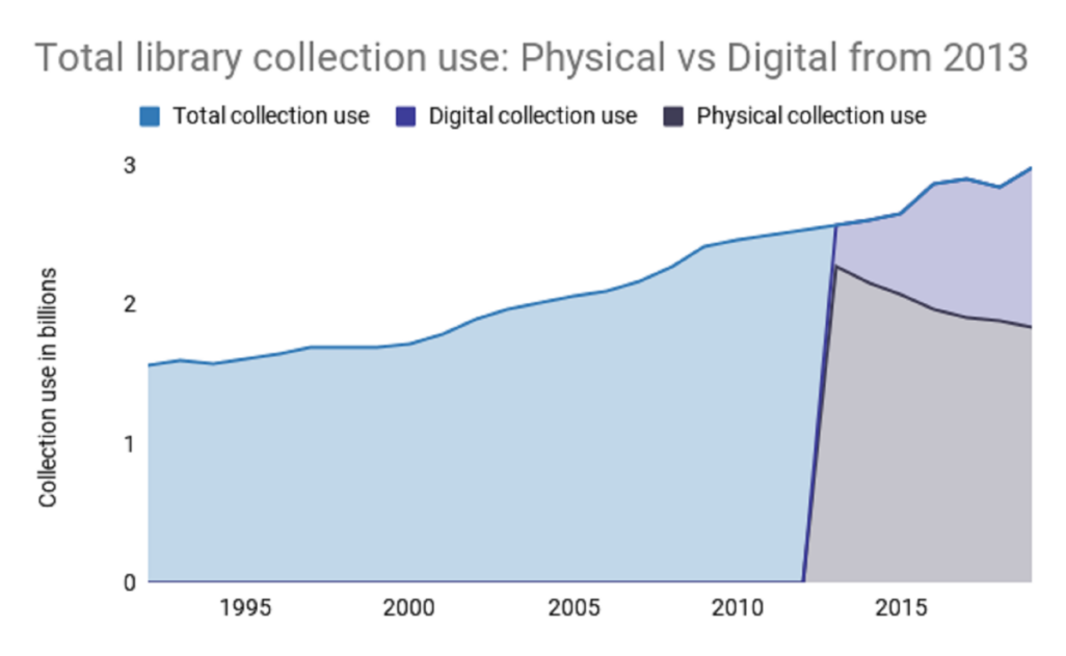

And we also have graphs like this, from the same article, which shows the sharp decline fully offset by an increase in digital borrowing:

The point is not to decide which of these graphs is right — the point is that the demand for our services is changing in a different way than it did before. We’re moving from a world like this, where our metrics are stable and controlled mostly by external factors like how many college students there are:

To a world like this, where our metrics have sharp bends in them and some go up while others go down, because of sudden shifts in what our patrons need:

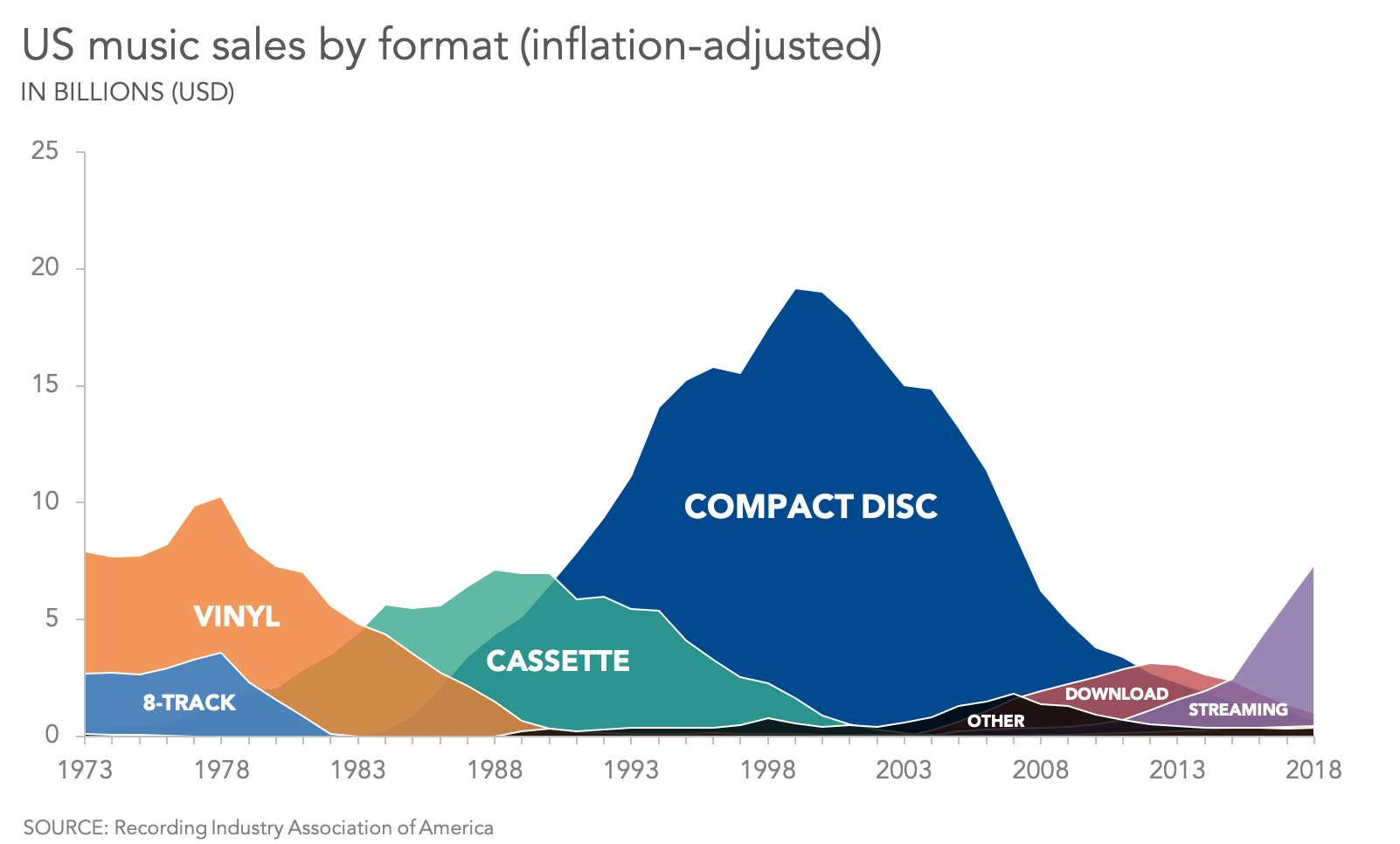

Or more realistically, something like this example, from Storytelling With Data, from the music industry:

We don’t know what the shape will be or where the sudden bends will lead — we just know that they’ll happen, much faster than before, so we need to learn to deal with sharp changes in the graph. And the lesson of Wikipedia is that we don’t get to complain about that: patrons do not owe us their patronage.

If patrons go off to solve their essential problems some other way, we don’t get to tell them not to. We never have. We either take the sharp turn with them, and become essential in the new places they live, or we stop mattering.

This isn’t news! Libraries have been working on this question for decades. Nicholas Hune-Brown recently wrote beautifully about the ways public libraries are learning to be “the last truly public space” and the history behind that struggle.

And it’s not specific to libraries. To take a nearby example, book publishers are stuck in a similar trap, where their profit margins are collapsing at exactly the time when they most need extra funds to find new ways of serving their mission.

But I think that trap is clearer and easier to see when it’s measured by a publisher’s balance sheet. What keeps me up at night is that libraries — especially university libraries — will be too slow to respond to changing patron needs, becoming less and less essential from the perspective of university administration, without seeing the trap clearly enough or facing up to what it means to be essential, and that we’ll shrink down to nothing.

What does “essential” mean here, in the sense Langdell made the Harvard Law School Library essential? It means something like, will giving the library less money result in lower quality admissions, lower quality faculty recruits, or less successful graduates? The way we shrink down to nothing is straightforward: on the one hand, we shift from “loss leader” to “cost center,” shifting from something that is essential to the school to bring students in the door, to something that deans push to spend less on each year. Cathy Eisenhower wrote about the changing pressure for university libraries to turn a profit, for example, in Inside Higher Ed back in 2010.

And on the other hand, we shift from “curator” to “contract negotiator” — we no longer use librarians’ distinct professional skills, ethics, and competence to choose what to acquire, and thus define the substantive fields we work in, but instead subscribe to a much smaller list of databases curated by commercial vendors with very different goals and values. The things that are essential to us — things like building collections for the long term, and not just until the publisher changes the subscription terms — are no longer in our power to control.

Escaping the trap: adopting a new mission

So we need a mission that makes us essential — just like Langdell announced the mission of being the “laboratory for the law” in 1870, or public libraries have worked to adopt a new mission as the “last truly public space.” What is the mission for university libraries?

Your answer will be better than mine, but my pitch today is that our essential mission is to be the home for cultural memory.

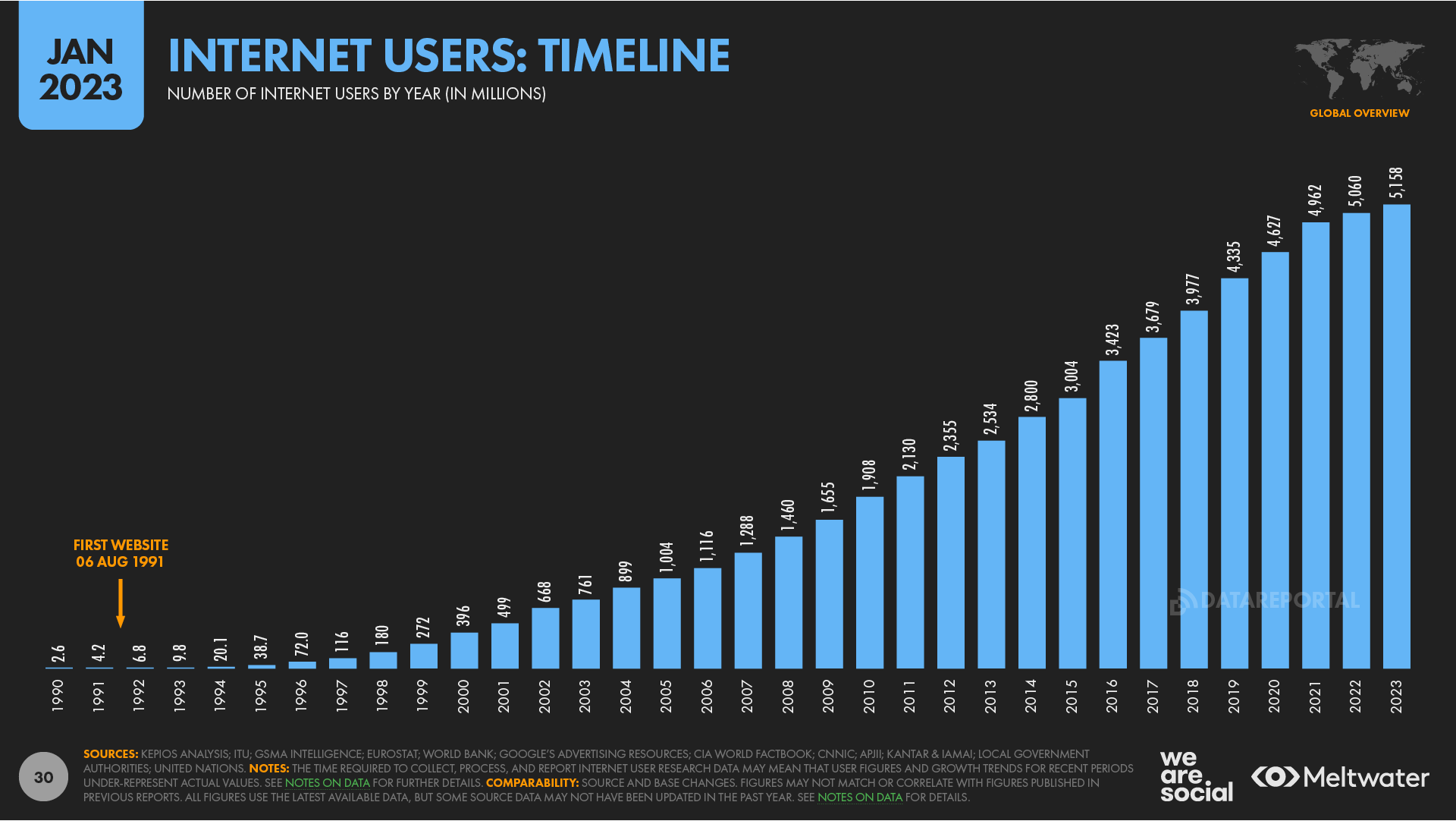

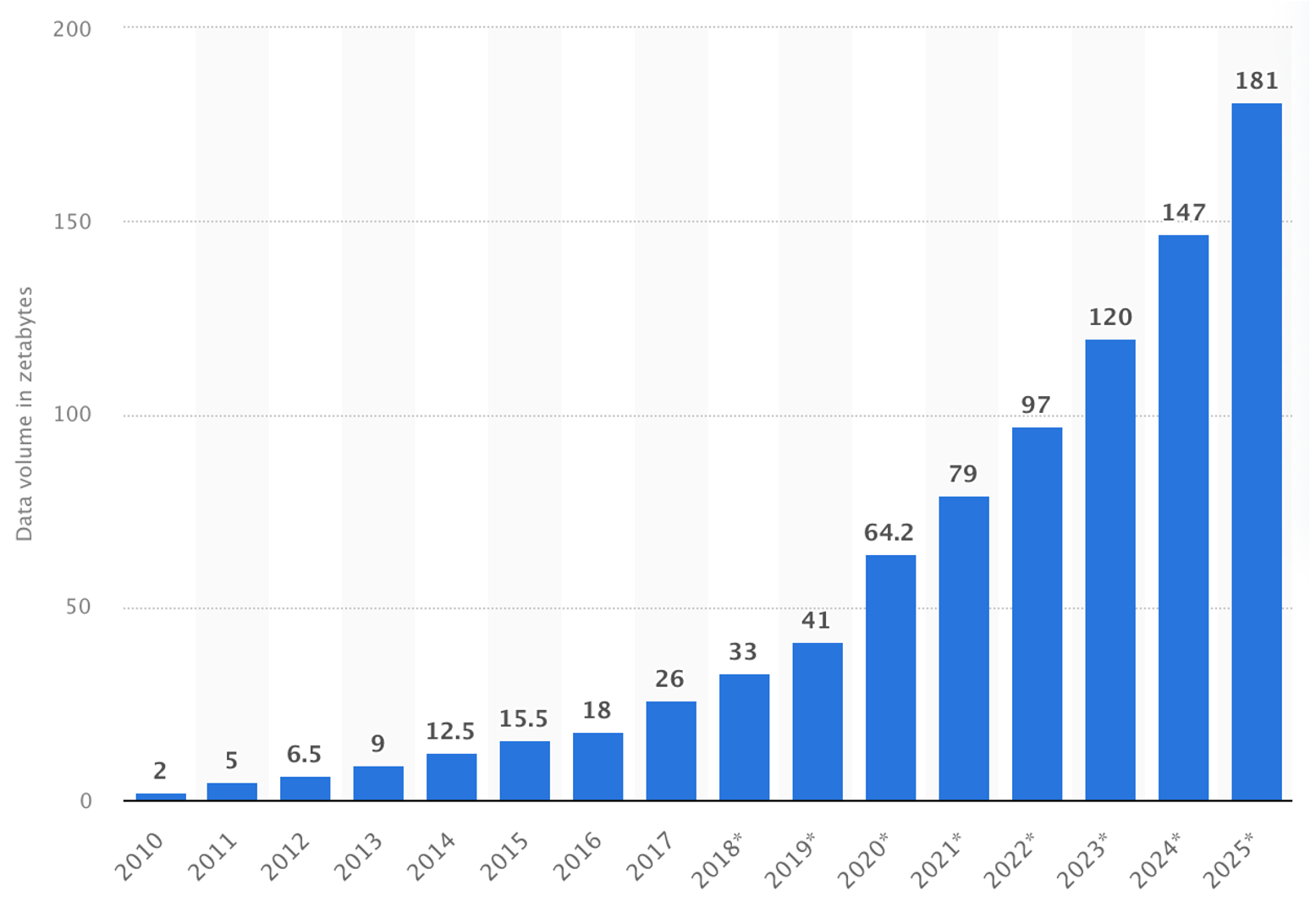

Five billion people have connected to the internet in the last 30 years, generating millions of petabytes of data per year.

But librarians know that data doesn’t make a library. Writing data to disk doesn’t mean collecting or curating knowledge; storing data doesn’t mean preserving knowledge; accessing data doesn’t mean access to knowledge.

Doing those things well — collecting, preserving, and accessing knowledge — gives us cultural memory. It gives us the ability to remember, plan, and pursue shared goals.

It’s easy to feel the opposite of that today — that connecting five billion of us with instant communicators, and generating zettabytes of data a year, has created the inability, at a large social scale, to remember truthfully what has happened, make coherent plans, or solve problems that require us to coordinate. The internet when it isn’t working feels like cultural dementia.

(I’m not saying, for purposes of this talk, whether our “cultural dementia” is better or worse than it was before the internet — the truth has always been hard to discern, and social coordination problems have always been hard to solve. But it certainly is a palpable problem today.)

Libraries are extraordinarily good at helping with this — they’re one of the few technologies where, the more of them you have in your society, the stronger, the more robust, the more flexible, the more resilient you get.

So when the Library Innovation Lab innovates, when it tries experiments, that’s what I’m looking for — what are the ways that we can strengthen cultural memory? Like:

- Perma.cc, which literally repairs cultural memory by fixing link rot in court decisions and law journals — and now offers tools.perma.cc, which lets any library or archive run their own web archive with the policies that matter to their communities.

- OpenCasebook.org, which lets law faculty collaborate on their own open source casebooks to reinvent the legal curriculum.

- Case.law, which digitized seven million court decisions, and built a wide variety of interfaces around those decisions, to let everyone in the world explore US caselaw.

- … and our new experiments in AI, which are once again focused on how to guide a new technology to have it help, rather than hurt, our ability to communicate and reason as a society.

We’re a small lab, and the things we can try are a small slice of the many ways libraries can explore novel missions. So for the rest of the talk, I’d like to share a grab bag of things I’ve learned about how to build a team that can respond to sharp changes in the graph and try something new.

How to build an innovation team — what I know so far

OK, so you’re on board with the idea that libraries should get themselves out of the disruptive innovation trap, by building teams that can test new and essential missions for their larger institutions. How do you do that?

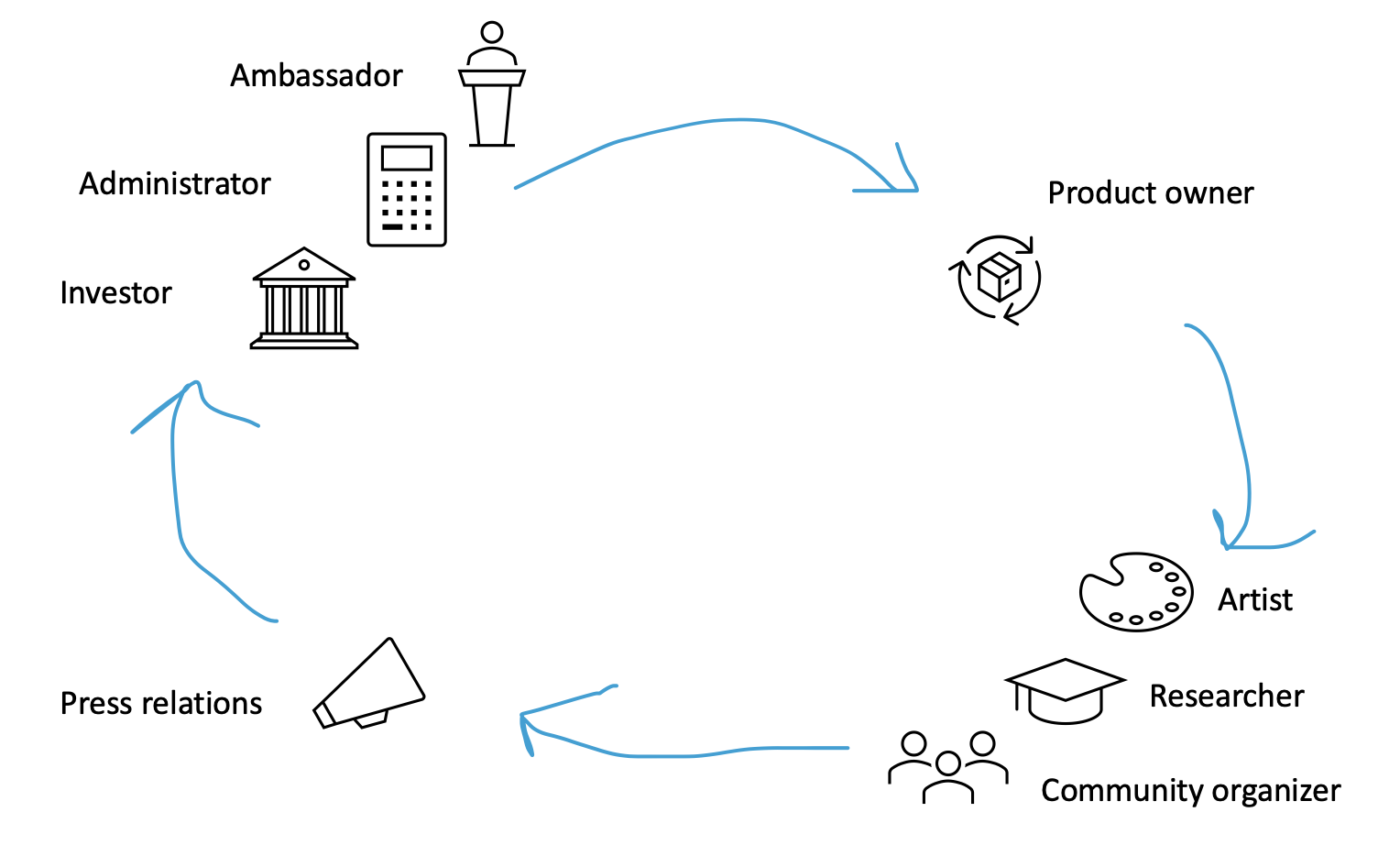

You don’t have to be the size of Harvard to build an innovation team. The trick is to start with the resources you have, and build a loop that helps you grow:

- Start with existing staff — your staff are innovating already, so you can start by just recognizing that and acknowledging it as part of their work.

- Get easy wins — practice identifying new things you are doing that can be polished and announced.

- Welcome participants — take the new projects, find people positively affected by them, and bring them into the conversation.

- Tell your story — when you have small successes, broadcast them to build support for your work.

- Grow resources — once you broadcast successes, use them to bring in more resources, which let you take on larger changes.

When you have this process up and running, the skills you are using will go in a loop something like this:

This won’t necessarily be eight people! It might be one person wearing eight hats. But if it’s working it will need skills like those eight people, so let’s talk through what these roles are bringing to the team:

Your product owner is responsible for placing bets and seeing them through. They keep track of what resources the team has to spend on getting things done and what opportunities there are to spend them, and they’re obsessive about making an impact.

Once bets are picked, your artist is an enthusiastic, optimistic creator who likes making new things and learning new skills. This could be a literal artist or a metaphorical artist — a programmer, a lawyer, a reference librarian, etc. — but someone who loves making the next thing.

Your researcher helps to measure your audience and your success and make what you learn replicable — what is the need we’re trying to fill, how well are we filling it, and how can we share what we learned?

Your community organizer is building relationships around your work — who are all the people affected by what you’re doing, and how can they be better informed and involved and represented? This job has lots of different names in practice, maybe “outreach” or “support.”

As cool things are made, they then need to be talked about. Press relations uses all of the cool stuff, the research about the cool stuff, and the relationships around the cool stuff to tell public stories about the cool stuff.

And finally, those successes feed back into your relationship with the larger institution that supports you. Innovation labs in larger organizations have a bunch of different complicated relationships that require different skill sets:

Your investor is whoever backs your bets, financially and otherwise. Often this is a professor or dean in a university library setting. They need to be on board with the risks you are taking and ready to back your decisions.

Your ambassador navigates impacts of innovation on the rest of the organization as you explore new missions, engaging with leaders of other groups who might be sensitive to you getting out of your lane or entering their territory.

Your administrator absorbs the new stress you’re putting on the larger organization, as the new things you’re trying to do put the bureaucracy through unexpected paces. (“I don’t know — how do we …” hire new kinds of people, take new forms of payment, get new kinds of permission from the trademark office, pursue new grants, enter new kinds of contracts — whatever it is you don’t usually ask for.)

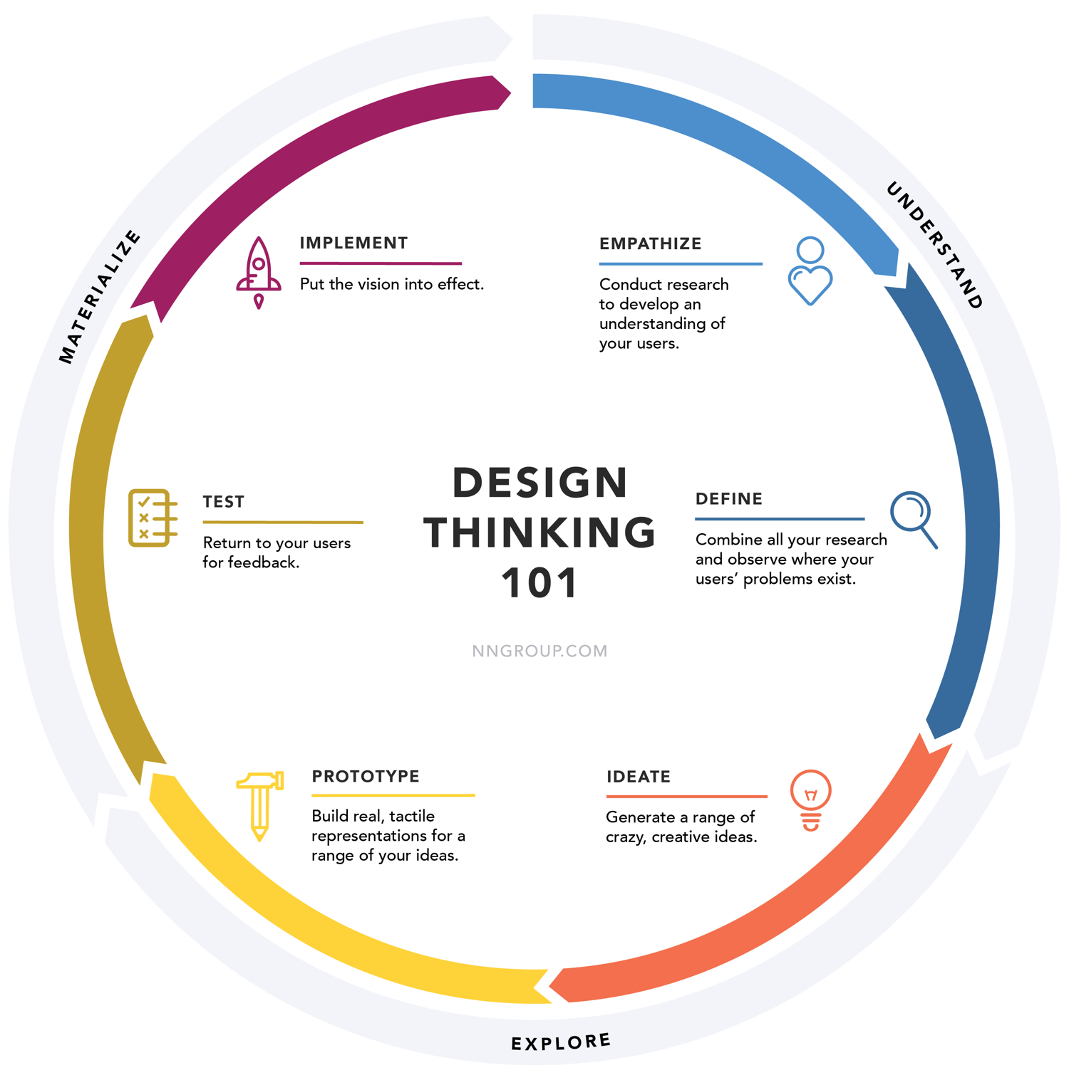

With all of this up and running, you’ll be well set up to do the kind of design thinking process that you’ll often see highlighted in innovation talks:

It’s worth learning the details of this kind of process, or complementary processes like co-design and design justice, but the most important high level concept is the shape: with our patrons’ needs changing faster than before, we need to build tighter loops between exploring, prototyping, shipping changes, learning how they work, and using that information to explore again.

The other thing a group like this is well set up for is to explore new business models. Remember that at the end of the loop is “grow resources” that can feed back into your team. When newspapers lost their traditional funding stream of classified ads, the successful ones didn’t just switch to one new funding stream, but to lots of smaller ones, so they would be shielded from the shocks of any one funding source disappearing the way classified ads did.

Likewise, there are a wide variety of funding models libraries can explore, including: grants; gifts; corporate partnerships; mixed paid and free services; consortial funding; donations; pro bono support; and more. Running a flexible product process will allow you to try all of these, and learn what works for the kind of problems you need to solve.

Ending things

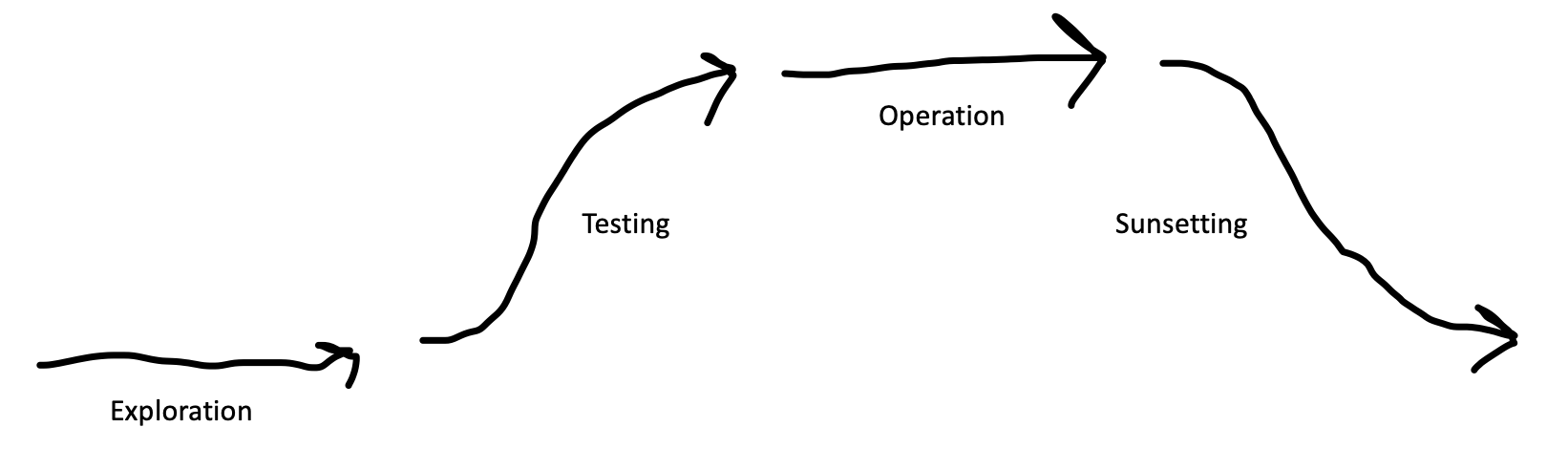

Finally I want to talk a bit about ending things. All successful ideas follow a course something like this:

An innovation team is best at the exploration and testing phases, and many library practices lead to excellence at the operation phase. But the phase I think is most important is the one we’re all bad at — sunsetting.

Patrons hate when we end things — there is always someone who deeply values whatever the thing is we were doing, and who can clearly articulate the values we were serving by doing it, and those are likely to be values we still honestly proclaim and hold. Ending things makes us feel like hypocrites.

But if we can’t end things well, we put impossible pressure on our operations teams to keep everything running forever, and in turn, those people end up stressed and understaffed and in no kind of mindset for exploration and testing of new ideas. We can’t do the rest well unless we’re good at endings — whether that’s ending near the beginning, in an exploratory phase where you have freedom to try and fail easily, or near the end, when you are helping a long term community understand that a service has to change.

I think the way we end things well is to focus on enduring values. Remember that the point was never to maximize the number of paper encyclopedias; the point was to be the cultural memory that strengthened our communities. It’s by articulating the underlying values we were trying to serve in the first place that we can best bring everyone on board with changes that are coming. We aren’t giving up, we’re moving on together.

We can’t avoid disruption, because our patrons don’t owe us their patronage and their needs are rapidly changing. But we remain necessary: we offer the cultural memory that allows society to function. So we need to build teams that can effectively test new ideas, and end old ideas, and do both of those by connecting, again and again, to the shared values that made all of this worth it: the values of building a public place where people can think, remember, plan, collaborate, and preserve the things that matter to them.

Thoughts? Email me at jcushman@law.harvard.edu.